Jab, jab, block, right hook — duck. Is it a boxing match?

No, it’s a communications campaign and you’ve got a front-row seat. For Americans, hearing companies snipe and jab at each other is a daily occurrence.

Verizon vs. AT&T, Apple vs. Microsoft (and vice versa), Wendy’s versus McDonald’s — the list is endless. As consumers, we may enjoy in some light schadenfreude as the highly produced and jam-packed advertisements flit by, but are they actually working?

The millennials have spoken

A quick survey of millennial friends (sorry- most of my friends are millennials) revealed that the answer is not so simple.

With such a wide array of views on brand rivalry, it’s surprising that companies are still choosing this technique. In recent years, Coca Cola vs. Pepsi, Nike vs. Adidas and McDonald’s vs. Burger King stand out in consumers’ memory.

What’s surprising is consumers recognize rivalries even among brands, such as Nike and Adidas who mostly have it out on the pitch, that avoid direct confrontation, in addition to the overt rivalries between social media provokers like Burger King and Chick-fil-A.

Burger King’s tweets have been gloves off, even offering to honor a discount promotion offered by McDonalds and lead the consumer to the closest Burger King instead.

If that’s not a good application of mapping software for brand rivalry, I don’t know what is.

But respondents’ opinions on what makes a convincing message are highly subjective. While some respondents preferred “data driven statements,” others liked “playful brand communication,” the cleverness of the campaign and “humbling acknowledgment of their rival.” Many agreed that the messages should be honest and give accurate insight about how competing products differ.

Survey: https://surveymonkey.com/results/SM-6LCK5ZPG7 (Respondents=15)

The takeaway from all of this is that any brand considering brand rivalry style of communication should make it appropriate for the TPO, their brand image and industry. Is it just me, or have we seen a drop in overt brand rivalry since the start of the pandemic?

It seems that there are bigger fish to fry in the advertising world.

Standard practice in the U.S. is tentatively adopted in Japan

Momotaro (Peach Boy) Goes to Devil Island

In Japan, comparative advertising has been historically avoided due to business practices. Overt comparison is distasteful and advertising agencies haven’t necessarily limited themselves to representing only only client in each industry, as is popular in the U.S. (Hence the creation of “conflict shops,” the creation of separate agency brands to give competing clients different representation)

In 1987, the Japan Fair Trade Commission loosened regulations and established three rules for comparative advertisements, thereby effectively acknowledging and allowing them in Japan.

While outright comparison is still largely taboo in Japanese culture, indirect comparison can be found if observing closely. One good example is the 2017 ad campaign for Pepsi (whom you might remember as launching the “Pepsi Challenge” during the Cola Wars period of 1970s -1980s) themed on the traditional fairy tale “Momotarou (Peach boy).”

It is often said that comparative advertisements are the weapon of the underdog — and in this case Pepsi embraced that image.

Momotarou is a boy born from a peach who has adventures with various animals until finally visiting demon island and slaying the powerful demon. While tapping into the image of Pepsi as a scruffy underdog (Momotarou) the 5-TV-commercial series drums up the viewer’s sense of righteousness and excitement with movie-like production values and the actor Shun Oguri.

Though Coca Cola never enters the picture directly, anyone with prior knowledge of the Momotarou legend and the red demon defeated in the end will have no difficulty connecting this ad campaign to the battle in the real-world soda industry.

Pepsi took it a step further by making the commercial itself “user generated content” by casting Pepsi drinkers in the final episode.

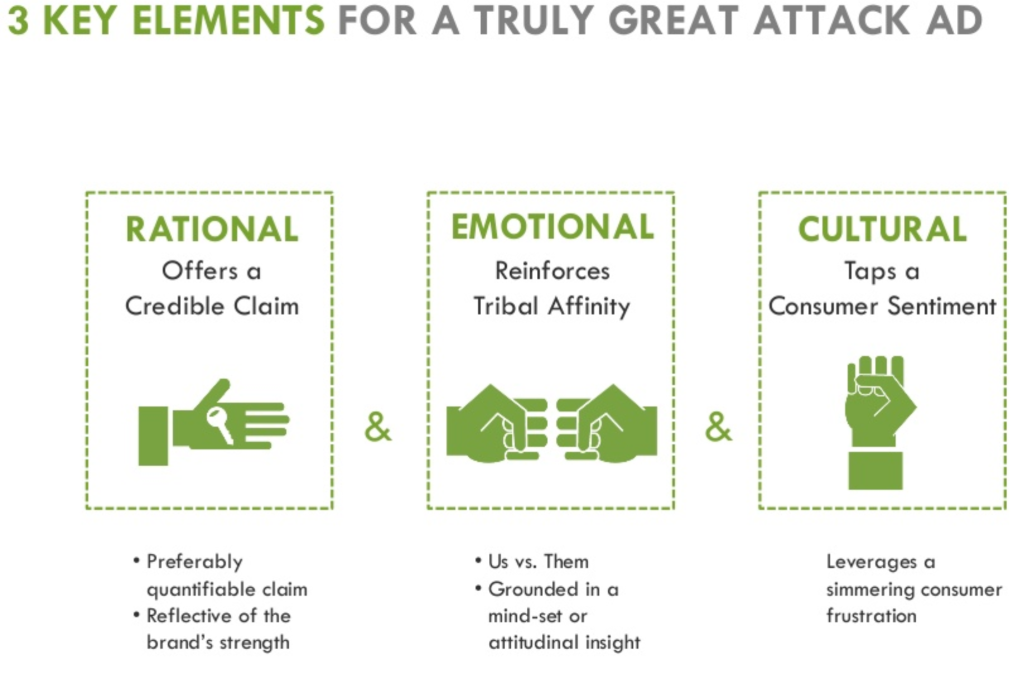

The success of this commercial can be attributed to its incorporation of the three elements of successful brand rivalry (attack ad) content and adaption to Japanese communication culture: high context, low (direct) confrontation.

Does brand rivalry really exist in Japan?

During a short presentation on U.S. brand rivalry, Japanese PR experts in my professional circle agreed that indeed the brand rivalries of the U.S. were a form of communication in and of themselves, effective at leaving strong impressions. But when it came to Japanese brands, brand rivalry is an unpopular style, they emphasized

Even comparative advertisement, as noted above, wasn’t clearly allowed until 1987, after so-called “external pressure” 外圧 from foreign brands looking to apply the technique to the Japanese market.

But is it really true that Japanese brands don’t leverage antagonism to make their own brands shine? I posed the question to my Japanese colleagues.

Example 1: In-group rivalry

Best exemplified by idol groups like AKB48, Nogizaka 46 and Kanjani 8, idol groups are the perfect place for building engagement between fans via the rivalry of members. AKB48 and Nogizaka 46 perfect this by holding annual “elections” where “centers” (leaderes) are elected, resulting in tearful and grateful acceptance speeches.

Example 2: Corporate monologue

Unlike dialogues in Western culture, Japanese debates are traditionally a long monologue in which the speaker expresses a series of opinions, explains Professor Yasushi Ogasawara of Meiji University.

Certain types of advertisements by Japanese companies can be categorized as this monologue-type of debate. An example from the Nihon Keizai Shimbun:

In this example, advertiser Iwatani asks the reader to question if the human race has the energy to power the next 100 years, then espouses the benefits of hydrogen: it doesn’t dry up, it can be used to power cars and send people to the moon, etc. It is a monologue against society’s current energy choices.

Example 3: “Domestically produced” appeal

The Japanese consumer considers “made in Japan” to be a guarantee of quality, and for no small reason. Standards for quality are high in Japan, and Japanese manufacturers work hard to meet them. As more imported goods, especially food, enters the Japanese market, Japanese manufacturers have to fight off foreign brands sold at cheaper prices.

One standard approach is the “made in Japan” appeal. Take for example, this advertisement created by Japan Agriculture (JA), the huge cooperative that buys and helps distribute the products of small-scale farmers and other food producers. (For more about how JA works, see this great blog post on Hackerfarm)

It superimposes a white monologue of text over a sukiyaki pot filled with presumably domestic ingredients. A summary translation of the text follows.

“Japanese people tend to purchase domestic only when they are worried for their safety

Food problems are prominent in the news now. Yet while you might check production area from time to time, most of the time you are probably purchasing the cheapest choice, imported from abroad. Actually, more than half of our food is imported from abroad. The more we choose imported food, the more our food self-sufficiency rate drops. To prevent this problem, we all need to purchase more domestic ingredients — after all, Japan is blessed with the environment to grow many different delicious ingredients. JA Group will continue to strive to support local farming and communities so that it can bring safe domestic ingredients to consumers.”

My Japanese colleagues were put aback by this example. “It’s just encouraging consumers to support their own country’s products — it’s not necessarily nationalistic or rivalry,” one man commented.

But look closely, and you can see how the advertisement lays out the pros and cons of the products on both sides of the dichotomy of domestic v. foreign, while also calling on the three key elements for a good attack ad: rational, emotional, and cultural. Sure, the ad doesn’t include an overt comparison of any product in particular, but it does acknowledge the antagonism of domestic and foreign-produced products, while encouraging the false impression that all foreign-produced products are less safe than those that are domestic-produced.

Ad campaigns and messaging plans are merely an extension of the varied rhetorical devices developed over centuries of human interaction, taking advantage of the cultural, emotional and rational triggers inherent to us humans. Take a closer look at the messaging around you and you’ll find there is more than meets the eye.

Feel free to comment or message me with your realizations and thoughts about ads, messaging, and rhetorical tactics in the public sphere!